For the past several years, I have devoted space in my garden for a monarch butterfly habitat and have raised and released butterflies at the end of each summer. I learned quickly that rearing these glorious creatures is not for the faint of heart; it’s work and sometimes heartbreaking as caterpillars frequently fall victim to pests, disease, or injury. But when you get to see one of your butterflies open its wings and fly off into the blue sky, it’s like getting a glimpse of heaven, making it worth all the effort.

For the past several years, I have devoted space in my garden for a monarch butterfly habitat and have raised and released butterflies at the end of each summer. I learned quickly that rearing these glorious creatures is not for the faint of heart; it’s work and sometimes heartbreaking as caterpillars frequently fall victim to pests, disease, or injury. But when you get to see one of your butterflies open its wings and fly off into the blue sky, it’s like getting a glimpse of heaven, making it worth all the effort.

If you are thinking about starting a garden for monarch butterflies or are just curious about the process, read on. Here I share my experiences and offer some tips based on what I’ve learned.

Among some of nature’s most amazing creatures, monarch butterflies breed throughout the United States and Canada, and then the last generation of each season migrates to Mexico and southern California where it hibernates in forests until spring. When the weather warms up, they migrate back to breeding territories. Of course, it’s a little more complex than this, and you can certainly delve deeper elsewhere if you’d like.

Milkweed is a Must

The cornerstone of a butterfly garden is the milkweed plant, which is the only food the monarch caterpillars eat. The butterflies lay their eggs on the leaves, and tiny caterpillars then emerge and feed on the plants until they are about an inch and a half long and a bit plump.

Once mature, the butterfly caterpillars produce a string-like fiber that adheres to a fence post, twig, or other fixed object, from which they then hang upside down in the shape akin to the letter J. After a few days they molt, forming a casing called a chrysalis, which is similar to, but different from, the cocoons formed by moths.The butterfly develops inside the chrysalis for a couple of weeks before emerging and unfolding its amazing wings. It then will hang upside down for a while as its soft floppy wings fill with a fluid that eventually hardens in an hour or two, making it possible for the butterfly to eventually fly. But if the butterfly wings don’t hang straight, they can dry deformed, and the butterfly is doomed. Accordingly, it’s essential to their survival that they hang undisturbed until their wings are ready for flight.

Because milkweed plants are poisonous to humans and can be invasive, farmers and homeowners over decades removed them from their farms and gardens leaving less habitat for the butterflies, which may be a key reason why monarch butterfly numbers declined over past decades. Recognizing the problem, people began to replant milkweed in nature preserves, along highways, and even on farms in certain designated areas, to provide much needed habitat.

Like many other homeowners, I decided to do my part by planting a milkweed garden. I planted a large patch thinking it would not be too difficult, and the larger the garden, the better it would be. Yet during the first two years of my milkweed garden, I only saw two caterpillars, and I am not sure if they ever became butterflies. In addition, I discovered the milkweed garden would go from beautiful in the spring to wretched toward the end of summer. The plants become gangly, with yellowing leaves as an army of small orange aphids devour them, which are very hard to control. You can’t use any pesticides, because you don’t want to harm the butterflies, and so, in addition to aphids, the garden can become a local salad bar for a wide range of obnoxious bugs.

In my third year, as I was about to throw in the towel, I noticed a few caterpillars crawling along and eating the leaves, so I left my messy, pest-ridden garden as it was. Eventually, I found another caterpillar, and another, and still another. They were appearing everywhere, munching away on my yellowing milkweed plants.

Additional Threats

Along with the caterpillars, the number of pests exploded, particularly the tachinid flies, which lay eggs in the caterpillars, turn into maggots, and then kill the caterpillar from within. Apparently, tiny wasps also find their way into the chrysalises and kill the monarch at that point too. As a result, I found a number of dead caterpillars as well as damaged chrysalises on my fence.

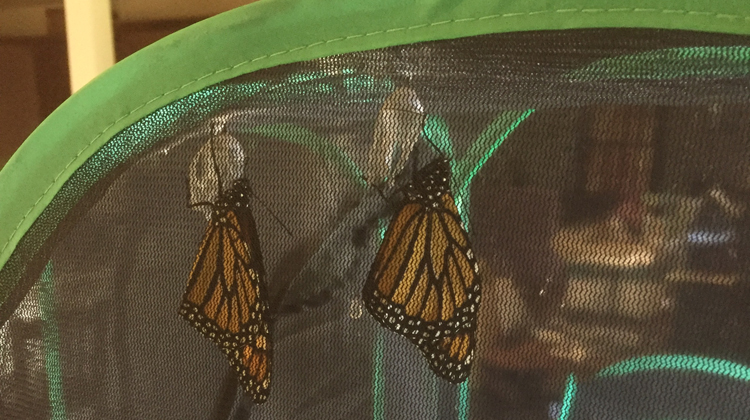

Because of such challenges, I’ve read that something like 90 to 95 percent of caterpillars never even make it to the butterfly stage! Despairingly, I bought a few butterfly cages from Amazon.com and found a few tiny caterpillars and some eggs to bring inside and place them with milkweed cuttings in one of the cages. I hoped that maybe I could save a few butterflies.

I also had learned that it is better to bring eggs rather than caterpillars inside, because tachinid flies may have already infected the caterpillars. I had several cages, keeping only two or three per cage. After a few weeks, one at a time, the caterpillars formed their chrysalises on the tops of the cages. I eventually released about six butterflies from those cages that year.

Finally, I had reason for some optimism.

In addition to the butterflies I raised indoors, several managed to grow to maturity by hanging on my fence that year as well. In total, I found seven chrysalises on my fence.

One morning I awoke to find that one butterfly had just emerged, but as I watched, he fell off the fence and started to get tangled in the grass. I had to act fast, as this butterfly was beginning to roll around the grass potentially damaging his still developing wings. I put my finger near the legs without getting too close to the wings. He climbed on and hung off my finger until I could relocate him to a safe twig on my crape myrtle. After an hour or more hanging and drying, he opened his wings, and I could see dots on the wing that identify a butterfly as male.

Meanwhile, I saw another emerging from a chrysalis, that I had not noticed before. It was inside a tangle of clematis vine. She got stuck and her wings were already damaged before I got to her. I did get her out, but it was too late. I located her to a vine where she could hang, and I hoped for a miracle. But she did not survive; it was heartbreaking.

A third butterfly emerged around the same time from a chrysalis on the fence. This time I had placed paper towels on the ground under each chrysalis thinking they would have a better chance of getting up and finding a place to hang than if they fell into the grass or garden mulch. In any case, butterfly number three did not need assistance. She hung on the fence and fluttered down and hung out on the paper towel, then on to a shrub. The four other chrysalises had succumbed to pests, and butterflies never emerged.

For the next couple of weeks, I watched these butterflies and the ones I raised indoors enjoy the nectar from my garden flowers. But once a fall chill was in the air, all the butterflies were gone in a flash. Off to Mexico!

The following year I changed how I kept my milkweed for the butterflies. I moved the plants into pots that I could move around rather than create a concentrated salad bar for pests. I also planted a variety of nectar producing flowers around the pots. That year, I raised even more butterflies—a total of 10 indoors—and had fewer pests. I also planted fennel and had dozens upon dozens of swallowtail butterfly caterpillars, which need fennel, dill, or parsley to reproduce.

If you are thinking about planting milkweed for the monarchs, that’s great! Based on my experience, I have some tips and suggestions, and you can research this more online. There are lots of helpful sites, and several are linked at the end of this article.

Whether you raise the butterflies in addition to providing habitat is up to you. There are some researchers who maintain that raising butterflies in cages could have a negative effect on their populations because they tend to be weaker than those that survive in the wild. Other researchers find that, if people do it right and responsibly, raising monarchs in protective cages can be helpful to the population’s survival. The issue is hotly debated, so I don’t have a good answer either way. One thing is certain: Anyone raising them should take steps to reduce risks of disease and produce the strongest butterflies possible. Some advice for that follows within the tips below.

Try planting milkweed in pots or not having such a concentrated area, as I did. I think the big patch I had attracted every pest in town, so mixing the milkweed in with other plants or putting it in pots may be better. If you have a big, concentrated milkweed garden, you may get frustrated with the way it looks, as caterpillars will devour the plants and leave a surprising amount of poop everywhere! You may also have to deal with nasty flies and other pests that show up to eat the caterpillars. Accordingly, I suggest you plan carefully on size, location, and concentration.

Understand there is a difference between annual and perennial milkweed. You can get annual milkweed or perennial versions, offering many options, flowers, colors, and foliage shapes and sizes. Perennial plants send runners underground into other garden beds, so they require some management. The annual version may be easier, and you don’t have to worry about it being invasive because it dies each year. However, there are some concerns to consider regarding annual milkweed. Some people say it’s not a good plant to have because it is a more vigorous grower and lasts longer into the fall, so butterflies will stick around too long and won’t migrate. In our area, annual milkweed should die down in the fall because it gets too cold, but late in the season, you should cut it down or pull it out so that it’s not a problem.

Control the seed pods. When the milkweed is done flowering, it forms numerous seed pods that eventually break open to release seeds attached to fuzzy materials that transport seeds far and wide. If you don’t control them, you will likely find milkweed growing where you don’t want it, and every year it will become more invasive as it sends runners all around your yard. So consider cutting off the seed pods before they crack open, which is what I do, to control the spread and prevent them from invading your neighbors’ gardens.

Protect your pets and yourself. Be careful to keep pets away from your milkweed, so plant it in an area where they cannot access it. Handle it with care, as it can even lead to temporary blindness if you get the milky sap in your eyes.

Recognize there are limits to pest control. Since you can’t use pesticides on the milkweed, pests will be hard to control. You can find advice about picking milkweed bugs off the plants and washing the aphids with water or squishing them with your hands, but they will come back. Personally, I find that a smaller more diverse garden worked best with all my perennial milkweed plants in containers.

Don’t raise too many butterflies. Although you might have dozens of caterpillars, putting more than a couple together in a cage can contribute to disease spread. For me, I can’t handle raising much more than about 10, but it’s usually less than that. If you want to raise more than a few, you will need multiple cages, and you might want to keep them in different locations. Right now, there is great concern about the spread of the disease known as Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE), which is contagious. You don’t want to harbor the disease in cages and then release sick butterflies to infect others in the wild. If you happen to have a butterfly that appears sick, don’t release it into the wild, and keep it away from other butterflies you are raising.

Consider putting cages in a safe outdoor location. Many people keep their caterpillars indoors, and that may well be fine. But some researchers suggest keeping the cages in a place outside is better because it’s more like the wildlife environment where they can experience natural light, humidity, and temperatures while still being protected from pests. If you do place the cages outside, make sure they have something heavy inside to keep them from tipping, and make sure they have some cover from heavy downpours and wind. A screened/roofed porch or a carport seems ideal.

Try to bring in eggs or only the very tiny caterpillars. Ideally, if you can find the eggs and bring them in before they hatch, you will more likely have healthy caterpillars. But it is hard to find the eggs as they are tiny, so focus on bringing in caterpillars when they are super small.

Practice good hygiene. Make sure cages are clean before you use them and are maintained while you house your caterpillars. Maintenance means cleaning the poop, and caterpillars make a lot of it! I use a hand vacuum at least once a day to clean it from the bottom of the cage. Cages should be washed with a light bleach and water solution once you release the butterflies and before adding more caterpillars. Usually, you will only have a couple in each cage for an entire season, but make sure you sanitize the cages before using them again.

Consider using potted milkweed to feed caterpillars in your cages. You can bring milkweed cuttings into the cage for the caterpillars to eat, but the cuttings can wilt quickly, and it’s a constant job to keep them fresh. I found that putting a small potted milkweed plant in the cage worked great. This year, I plan to grow some in an inexpensive plastic greenhouse I purchased, so I will be ready for feeding with aphid-free plants when I have caterpillars to feed indoors.

Here are some good websites for research purposes:

The Monarch Lifecycle. This site is full of great information from plants to raising butterflies to controlling disease.

Butterfly Farms. This page has some good information about pests and how to control them that you need to understand.

Project Monarch Health. This site has excellent information on OE and other diseases.

You can get cages at Amazon.com. I chose the kind that pop up and are tall enough to put a potted plant inside. Something like this. The ones I purchased are about 23 inches high. You can get bigger ones, but they are harder to manage, and I think it’s better to have more cages with fewer butterflies in each. Larger cages may be good for raising plants without pests to use as food.

It’s a bit late now to start a milkweed garden from seeds this year, but buying a few plants from a local nursery can get your butterfly garden up and running quickly! By August, you may soon see some caterpillars! For those who already have gardens, please feel free to share your experiences and insights about planting for and raising monarchs in the comment section.

Image Credits: All images were photographed by the author.

Angela Logomasini and her husband Christopher Prawdzik are licensed Realtors® with Samson Properties in Alexandria. Operating as D.C. Region Real Estate, they serve the Virginia, Washington, D.C., and Maryland real estate market and offer comprehensive real estate services, including 4½% full-service listings.